[ad_1]

This article, the second of a three-part series on how to implement an effective backdoor Roth strategy, was written by guest contributors Steven Jarvis, CPA, MBA, and Matthew Jarvis, CFP.

Continuing with the example with clients Bob and Sue from our first article, let’s assume they started and ended the year with no other IRA dollars (including funds in any Simple or SEP IRAs). Their only activity was contributing $6,500 to their respective traditional IRAs and then converting those funds into Roth accounts.

While the IRS has no specific rules on how much time must elapse between the nondeductible IRA contribution and the Roth conversion, the authors recommend having these transactions at least appear on two different statements (for example, separate months) whenever possible so that in the event of an audit, auditors can more clearly see the steps that were taken. Prior articles on Nerd’s Eye View have suggested time periods as long as 12 months. Again, neither one month nor one year is an explicit requirement, but the authors’ team has sat through IRS audits of backdoor Roths, and the cleaner, the better! It is important to remember on the other side of this that waiting too long can create issues as well. Any earnings that happen before the conversion takes place are taxable.

Nerd Note From Michael Kitces

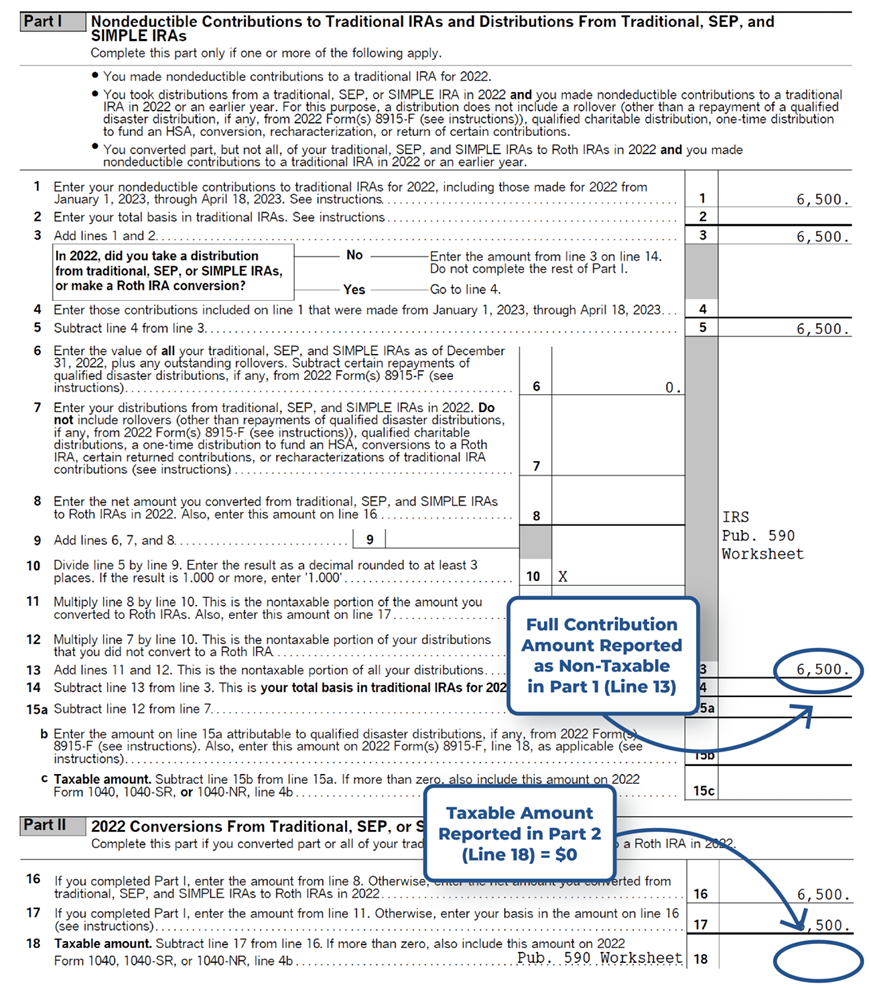

In Bob and Sue’s case, each would complete their own Form 8606 to be filed with their 1040. Parts 1 and 2 of the form need to be completed; the amount of the contribution will appear on multiple lines throughout the form but, in this situation, will ultimately end with the full contribution and conversion being reported as nontaxable in Part 1 on line 13 and with line 18 in Part 2, which asks for the taxable amount, being blank.

When a backdoor Roth contribution like the one described above for Bob and Sue is executed and reported correctly, there is no impact on taxable income. However, the conversion amounts will be reported as a “distribution” on line 4a of Form 1040 (while being left out of line 4b because it’s a nontaxable conversion of aftertax dollars).

It isn’t terribly uncommon to have a scenario as clean as Bob and Sue’s. For example, many advisors will have mass-affluent clients with all their qualified funds inside of company retirement plans, which are ignored for the purposes of calculating backdoor Roths (assuming the funds aren’t rolled over into an IRA during the year).

Commingling and Cream in the Coffee

Unfortunately, things get complicated quickly if taxpayers have existing IRA dollars (in any account) and/or if they plan to roll over funds from a qualified account at any point during the year. This is because of the IRA Aggregation Rule under IRC Section 408(d)(2), which stipulates that when determining the tax consequences of an IRA distribution including a Roth conversion—particularly the “pro rata” rule under IRC Section 72(e)(8) and also the early withdrawal penalty under IRC Section 72(t)(1)—the value of all IRA accounts will be aggregated together for the purpose of any tax calculations.

As IRS Form 8606 indicates on line 6: “Enter the value of all your traditional, SEP, and SIMPLE IRAS as of December 31….”

A common mistake made by taxpayers is to open a separate IRA account with the intention of “holding” the tax-free basis apart from other taxable IRA funds or assuming that a backdoor Roth can be completed midyear before they retire in the fall and then rolling over tax-deferred funds in their 401(k) plan into an IRA well after the midyear backdoor Roth conversion has been completed.

In either case, the IRS will consider these distributions as pro rata combinations of taxable funds and tax-free basis across all the client’s IRAs, which will turn a “clean” backdoor Roth into a messy partial Roth conversion. If the full amount of basis is not converted in a single year, it will have to be tracked and reported until the basis is fully converted or distributed. This creates a reporting requirement that could last for years or decades. In reality, the basis is often forgotten about, resulting in the taxpayer eventually paying taxes on a distribution of the basis that should have been tax-free.

Let’s say Bob, of Bob and Sue above, did a $6,500 backdoor Roth, which his advisor told him would be tax-free.

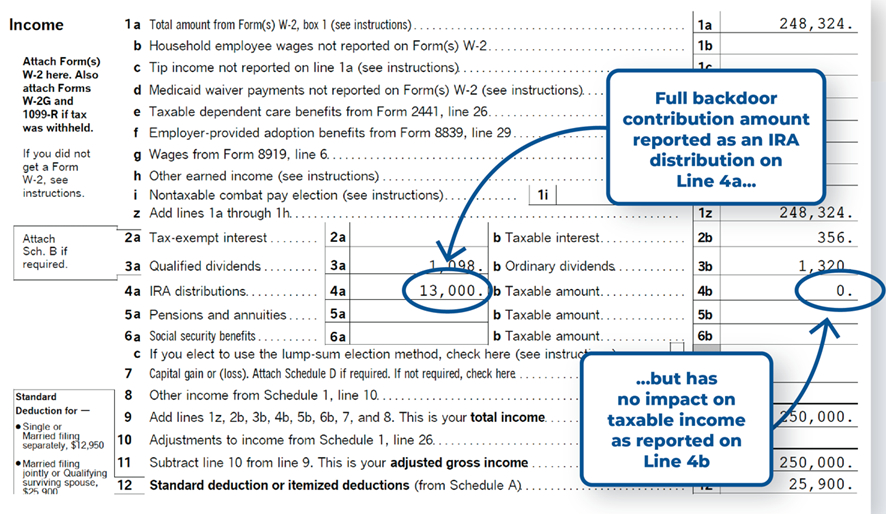

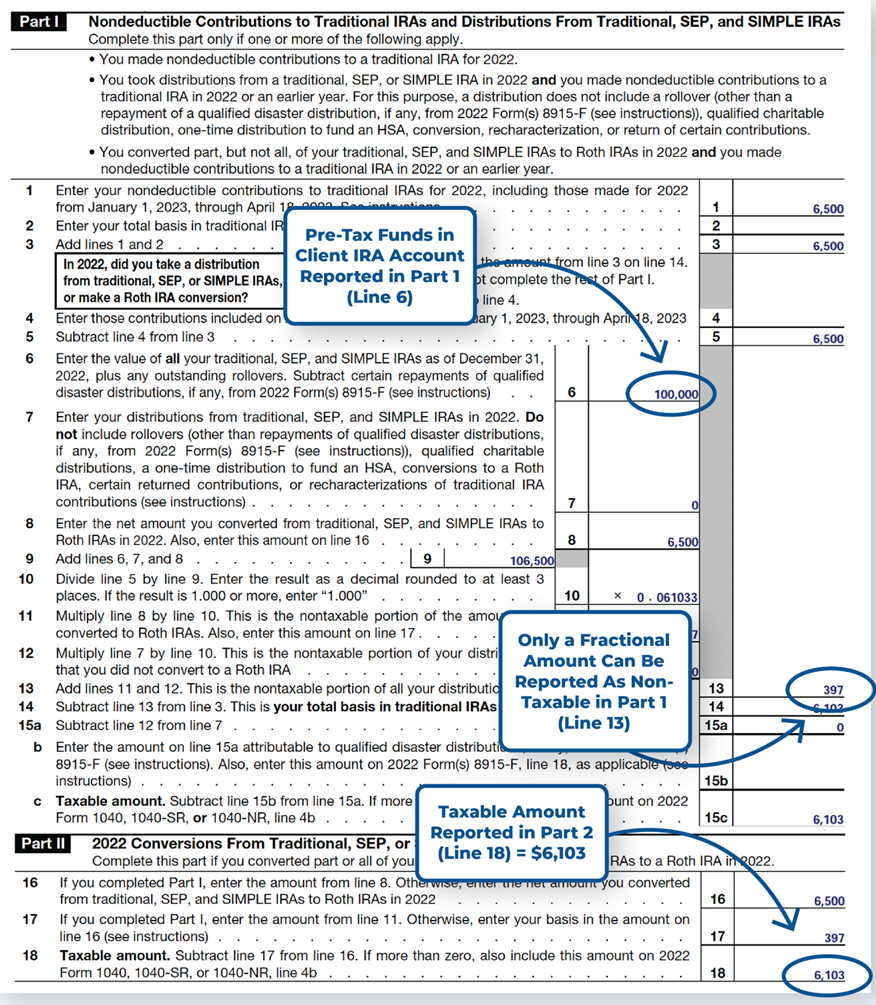

However, upon reviewing Bob and Sue’s tax return and accompanying Form 8606, their advisor discovered that the client had $100,000 of pretax money in another IRA (this becomes even more complicated if this isn’t discovered until years later).

Because of the $100,000 pretax and $6,500 aftertax balances, the combined total account value reported on Line 6 of Form 8606 would be $100,000 + $6,500 = $106,500, which means that every future distribution would be approximately $100,000 divided by $106,500 = 93.9% taxable and $6,500 divided by $106,500 = 6.1% tax-free.

So, instead of Bob’s $6,500 being converted wholly tax-free as his advisor originally thought would be the case, what actually happened was that only $6,500 x 6.1% = $397 was tax-free, and the remaining $6,500 – $397 = $6,103 was taxable!

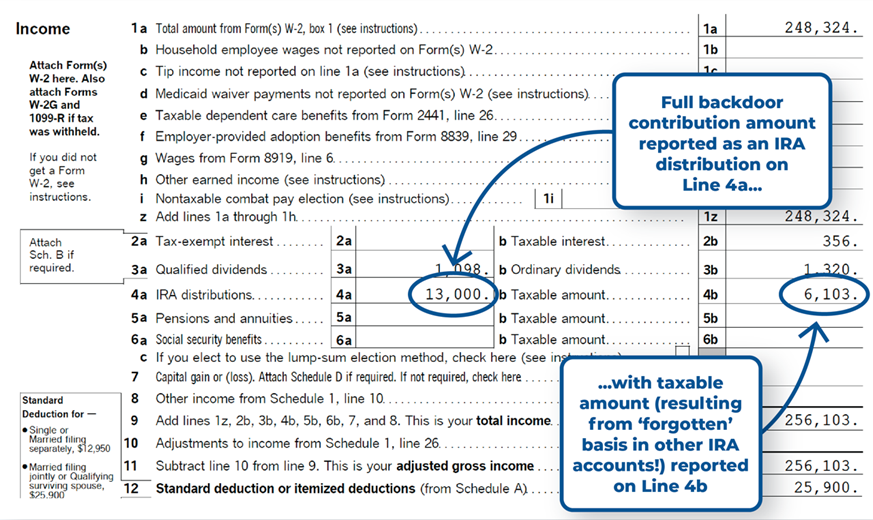

Instead of reporting $0 as the taxable amount for IRA distributions as originally intended, Bob and Sue now need to report $6,103 as taxable income on their 1040, as follows:

After Bob and Sue’s tax preparer corrects their tax return, the tax preparer tells them, “I’m not sure what your financial advisor was thinking, but they really messed this up!”

An awkward situation for Bob and Sue’s advisor.

Notably, this example only covers Bob’s situation because the pro rata rule is applied to taxpayers individually. Only Bob’s IRAs (including Simple and SEP IRAs) would be used to calculate how much of the conversion was, in fact, tax-free. If Sue had a $200,000 IRA as well, Bob’s calculation would not change, but Sue’s form 8606 would have to be updated to include her pro rata calculation.

This pro rata distribution rule is often referred to as the “cream in the coffee” rule, as once a person pours cream into their coffee, every sip is some portion of cream and coffee. Similarly, once nondeductible contributions are mixed into an aggregation of IRAs, every distribution (or conversion) is some portion of nondeductible and taxable. However, unlike a cup of coffee left to sit on the table all day, the “cream” of an IRA will never separate itself, and the taxpayer will be left with taking and reporting pro rata distributions forevermore, at least until such point they have effectively zeroed out all IRA accounts. Ouch.

To avoid this situation, before recommending a backdoor Roth, prior tax returns must be reviewed for Form 8606 to see if there is already some aftertax cream in the IRA coffee (which, sadly, is not always reliably filed; so even if Form 8606 wasn’t filed to indicate the presence of other IRA funds, the taxpayer may still not be in the clear to do a backdoor Roth). More importantly, advisors need to make sure they know about every IRA dollar, everywhere in all accounts, and they need to confirm that there will not be any rollovers during the remainder of the current year.

Accidental and Lost IRA Basis

Another common situation when taxpayers unknowingly end up with tax-free basis in their IRAs is when they were only partially eligible for a deductible traditional IRA contribution because their income was in the middle of the phaseout range, and, instead of reversing the excess contribution, the box was clicked in the tax software to simply leave the extra in as a nondeductible contribution. When this happens, the taxpayer technically has to file form 8606 continually for any year there is a distribution from their IRA to properly calculate and report the pro rata portion of the distribution that is tax-free.

More commonly, the basis is “lost,” meaning that it goes unreported and tax will be paid on the same income twice (once when it was contributed because the taxpayer did not receive a tax deduction, and a second time when it is distributed and reported as a taxable because no one told the IRS otherwise).

Not to pile on more complications here, but technically, filing Form 8606 is only required when there is activity to report. As such, if the taxpayer has basis in their IRA account(s) but hasn’t taken a distribution, made a contribution, and/or done a conversion in years, it could be years—or even decades!—since Form 8606 was included with their tax return. As such, advisors could easily review the tax returns from the last two years, not see a Form 8606 included, and incorrectly assume there was no basis to report!

To prevent this, getting even an oral history from the client describing their IRAs and reconciling that with their Social Security earnings statements to identify potential years over the limits can help advisors identify lost basis. The client’s oral history will at least provide context for whether they have ever contributed to an IRA, and reviewing Social Security statements allows advisors to see how much taxpayers reported as earnings by tax year, which can be compared with the income limits for making deductible IRA contributions to identify tax years that might be worth investigating. This may not be a perfect solution, but it is one that is more likely to be executed than trying to get tax returns for every single year a client has paid taxes. Admittedly, at some point, the light isn’t worth the candle of tracking this stuff down … until it is.

Given these complexities, it becomes easier to see why “everybody knows” about backdoor Roth conversions, yet few people actually understand all the complex nuances involved in doing them efficiently.

In our next article, we’ll discuss whether it’s necessary to completely zero out all IRA accounts before doing a backdoor Roth conversion.

Steven Jarvis, CPA, MBA, is the CEO and head CPA at Retirement Tax Services, a tax firm focused on working with financial advisors to change the world one tax return at a time.

Matthew Jarvis, CFP, is the owner and lead advisor of Jarvis Financial Services.

This article first appeared on the Nerd’s Eye View at Kitces.com and has been reprinted here with permission. The views expressed here are the authors’.

[ad_2]

Source link