[ad_1]

Melinda Caughill’s client was panicking. A medical incident had landed her in an emergency room, where doctors diagnosed her with terminal cancer. But that wasn’t all.

“In that same emergency room visit, the hospital administrator came in to deliver the even more whopping bad news,” said Caughill, a certified senior advisor. “‘Hey, you have stage 4 cancer, and oh, by the way, you don’t have health insurance.'”

As it turned out, the woman had missed her enrollment period for Medicare. Having lost her job about a year before, she thought she was covered by COBRA — the law allowing former employees to extend their health insurance — but she was not. Now it was June, and her next chance to enroll in Medicare would be in January.

In the meantime, she had begun emergency chemotherapy treatments, which cost about $35,000 a month.

For help, she turned to Caughill. The advisor and her mother, Diane Omdahl, are the co-founders of 65 Incorporated in Mequon, Wisconsin, where they run an unusual practice: They only advise clients about Medicare. That may sound like a narrow scope, but, thanks to the program’s complexity, it’s more than enough to keep them busy.

“The only thing in Medicare that is true for everyone is nothing in Medicare is true for everyone,” said Caughill.

On paper, Medicare has a simple mission: Provide government-funded health insurance for Americans aged 65 and older. But since it was enacted in 1965, the program has grown far more complicated. Today it includes three components: Part A, for hospital visits, home care and hospice services; Part B, for doctor appointments and other outpatient services; and Part D, for prescription drugs.

And those are just the public components. In addition, private insurance companies sell so-called Medigap plans, which supplement Medicare’s coverage, and Medicare Advantage plans — sometimes referred to as “Part C,” although they are not part of the federal program — which replace parts A and B.

The result is a maze of options, combinations and deadlines that can be overwhelming for seniors. And taking a wrong turn can be disastrous, as it was for Caughill’s client.

READ MORE: Battle of Part B: The long, messy history behind Medicare’s lower premiums

That’s where financial advisors can help. The average wealth management client is 64.2 years old, according to the consulting firm McKinsey & Company — and that number has been steadily rising. Americans become eligible for Medicare at age 65, so advisors can provide an enormous service to their clients by helping them navigate the program.

“I think it’s critically important for financial advisors to have a far better understanding of the Medicare system,” said Ron Mastrogiovanni, president of HealthView Services, a company that produces health care cost-projecting software for wealth managers. “This is an important feature that they should be able to offer as financial advisors, to help [clients] walk through that process — because most people have no idea.”

Medicare is not just a labyrinth; it’s an obstacle course. From enrollment deadlines to means-testing surcharges, the Medicare maze is riddled with pitfalls and traps. Below is a guide to the danger zones clients should be aware of, and the ways advisors can guide them safely to the other side.

When to enroll

The first thing a client needs to know about Medicare is when to sign up for it. But even for this simple question, the answer is not straightforward, and getting it wrong can be extremely costly.

For parts A, B and D, the initial enrollment period is the seven-month window around one’s 65th birthday — the birth month itself, the three months before and the three months after. For example, if someone’s birthday is in January, their enrollment window is October 1 through April 30.

But there are exceptions. First of all, if a client started collecting Social Security before they turned 65, sit tight — they’ve already been automatically enrolled in parts A and B of Medicare. And Part D is optional; if a client already has “creditable coverage” from another source — in other words, prescription drug insurance that’s just as good — they can use that instead.

READ MORE: 5 ways the Inflation Reduction Act could change life for retirees

But there’s also another, trickier exception: If someone’s birthday falls on the first of a month, the whole enrollment period moves up a month. For example, if a person’s birthday is January 1, their window is not October to April, but September to March. And if they miss it, their next chance is the general enrollment period — January 1 through March 31 for parts A and B, or October 15 through December 7 for Part D.

“Now, you might think that’s no big deal,” Caughill said. “But if you happen to be thinking you have one month left, and you find out that you’re done, that’s huge.”

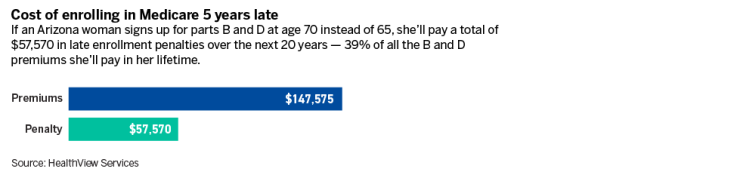

What happens if someone misses their initial enrollment period? There are two consequences: First, they pay a late enrollment penalty. For Part B, for example, that penalty is 10% of the premium for every year the person was late. This in itself is not an enormous expense — the Part B premium for 2024 is $174.70, so the penalty for being two years late would be $34.94 per month.

But for a senior on a fixed income, that can be significant — especially because the penalty extends through the rest of one’s life.

“It’s not a one-time penalty,” said Mary Johnson, a Medicare policy analyst at The Senior Citizens League. “That will be tacked on to your premium, and you will pay higher premiums for as long as you are in Medicare.”

The second, much larger consequence is that, while waiting for the next enrollment period, beneficiaries can be stranded without health coverage for months. That’s exactly what happened to Caughill’s client, who thought she would be covered by COBRA. But for people aged 65 and older, COBRA only acts as a secondary payer — the primary payer is supposed to be Medicare.

Just by informing their clients of this loophole, financial advisors can help them avoid disaster.

“COBRA is not considered continuity of coverage — don’t ask me why,” Mastrogiovanni said. “There are things like that that the advisor can bring to the party that are extremely valuable to someone who’s 65.”

Which parts to enroll in

Like all retirement planning, Medicare planning is all about thinking ahead. So when choosing which parts to enroll in, advisors can remind clients to sign up not just for what they need now, but what they’ll need in the future.

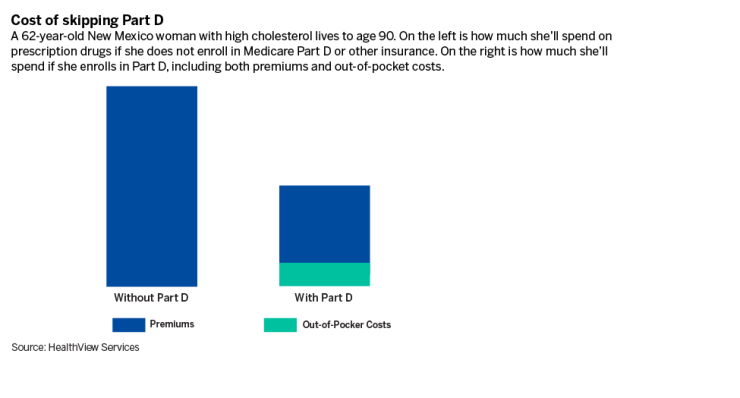

“Some people say, ‘Oh, I don’t take any prescriptions. I don’t need Part D,'” Johnson said. “Wrong! You do, and it’s going to cost you a delayed enrollment penalty.”

The late penalty for Part D is substantial: An additional 1% is added to the premium for every month that passes between when the person signed up for parts A and B and and whenever they finally sign up for Part D.

For example, if a senior signs up only for the first two parts of Medicare and then, five years later, realizes they want prescription drug coverage after all, their monthly Part D premium grows 60% bigger for the rest of their life. In 2024, that would mean an additional $33.30 per month.

All this can be avoided if the beneficiary decides whether they want Part D right when they first become eligible — and then sticks to that decision. To make a farsighted, final decision like that, they may need help from a financial advisor.

“Here’s what they could say,” Mastrogiovanni suggested. “‘You can buy a very inexpensive prescription drug plan [instead of Part D], but you don’t want to be in a position where you you’re going to need it.'”

Private plan options: Medicare Advantage and Medigap

The other choice is whether to get parts A and B — collectively called “Original Medicare” — or to get a Medicare Advantage plan instead. The key to understanding this choice is that Medicare Advantage does not supplement Original Medicare; it replaces it.

“Medicare Advantage is really a private form of Medicare,” Johnson said. “What the government does is contract with the insurer, give the insurer a lump sum and say, ‘Here’s what you have to cover.'”

What’s the case for Medicare Advantage? Sometimes these insurance plans cover health care costs that Original Medicare does not, such as dental care, vision and hearing aids.

But the important thing for clients to be aware of is the trade-off: While Medicare Advantage may cover these additional expenses, it often doesn’t cover Medicare’s core expenses — hospital visits and doctor appointments — as well as parts A and B. In 2023, 98% of U.S. doctors and practitioners accepted Medicare as payment, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The same cannot be said of Medicare Advantage plans.

“The important thing for people to know about Medicare Advantage is that these are private plans,” said Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the Program on Medicare Policy at KFF, a health policy research nonprofit. “They have networks of providers, in contrast to traditional Medicare, which, basically, you can go to any hospital or doctor.”

Medicare Advantage can also be much more expensive.

“The insurer has some leeway to charge you premiums if they want to, and they can charge co-pays for just about any service,” Johnson said. “They also can charge pretty much the way they want to for hospital care, which can be far more expensive than the other option.”

READ MORE: Ask an advisor: Will Medicare help care for my 97-year-old mother?

The other thing to remember is that, as American citizens, most seniors already pay for Original Medicare. Ninety percent of Part A is funded by payroll taxes, according to KFF. A quarter of Part B is funded by premiums — and for any client receiving Social Security, that premium is automatically deducted from their benefits.

“You already paid for A while you were working, and they’re taking B out of your Social Security check,” Mastrogiovanni said.

So what’s the advantage to Medicare Advantage? For the consumer, Johnson said, not much.

“It’s an advantage for the people who hold shares in the insurance company,” she said.

Instead, Johnson recommends something else: Medigap, also known as Medicare supplemental insurance. Like Medicare Advantage, Medigap helps pay for expenses not covered by Original Medicare. But unlike Medicare Advantage, Medigap doesn’t replace anything — customers can buy it without giving up parts A and B.

Johnson prefers this product so strongly that she uses one herself. The premiums are higher — hers is about $200 per month, while the average Medicare Advantage plan costs $18.50 per month, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services — but she believes the money she saves on health care makes Medigap worth the price.

“I think it’s better for people who have chronic conditions,” said Johnson. “I can go into the doctor’s office and walk out without ever paying any bills. There’s no co-pay or anything.”

Battling the IRMAA

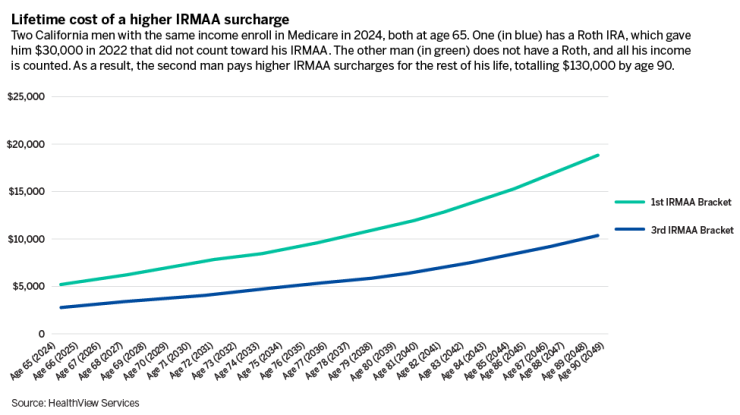

Medicare beneficiaries don’t just get charged for being late; they also get charged for being rich. That’s because of something called the IRMAA: the income-related monthly adjustment amount. This surcharge is added to the Part B and D premiums of Americans with high incomes — and for financial advisors with wealthy clients, it’s a very important thing to be aware of.

“The average client is emerging affluent or affluent,” Mastrogiovanni said. “They get means tested, so they have to pay more.”

In 2024, the income threshold for the IRMAA to kick in will be $103,000 per year (or $206,000 for married couples filing their taxes jointly). If a client’s income is below that amount, they don’t need to worry. But above it, the surcharge grows with each income bracket.

For Part B, a person (filing individually) earning between $103,000 and $129,000 gets hit with a $69.90 IRMAA added to their monthly premium. For someone making more than $500,000, the IRMAA is $419.30. If they spend about 30 years on Medicare, those surcharges can add up to more than $150,000.

For Part D, the IRMAA’s wrath is not as severe, but still significant. For a beneficiary making between $103,000 and $129,000, the surcharge would be $12.90 per month. And for someone making over $500,000, it would be $81 — which, over 30 years, would add up to $29,160.

The key to minimizing these charges is to understand how they’re calculated. Medicare determines a person’s income based on their tax return from two years before they enrolled in the program. So if a client is planning to sign up for Medicare in 2025, it’s important not to make too much taxable income in 2023.

Advisors can help clients make decisions with that two-year time frame in mind. For example, if a client is planning to enroll in two years, now is not a good time to sell their house.

“You don’t want to do that within the two years,” Mastrogiovanni said. “Even if you’re only going to be living on a small amount of income, if you’re making hundreds of thousands of dollars in capital gains during the sale of the house, you’re going to get clobbered.”

Another solution has to do with retirement plans. As a retiree begins withdrawing from their 401(k) or IRA, those withdrawals count as taxable income — unless it’s a Roth. With all Roth IRAs and 401(k)s, money is taxed on its way in as contributions, not on its way out as distributions. If advisors can persuade clients to switch to a Roth — during or before the two-year look-back period — they can make sure those distributions don’t trigger a higher IRMAA.

But for her clients, Caughill recommends saving in something else entirely: a health savings account (HSA).

“I’d say the thing you max out first and foremost is an HSA,” Caughill said. “It is the single best retirement account, because taxes never touch it.”

READ MORE: Everything you need to know about health savings accounts

The savings in HSAs are tax-exempt, both as contributions and as withdrawals — as long as they’re spent on health expenses. But Caughill doesn’t consider that a problem, because retirees spend an enormous amount of their savings on health care anyway. According to one study by RegisteredNursing.org, the average 65-year-old’s health expenses are about three times those of the average American in their 20s or 30s.

Mastrogiovanni highly recommends HSAs as well.

“If you save it, and you use it for health care, it is not considered income, and doesn’t fall under surcharges,” he said. “The positive impact that that could have is pretty significant.”

All of these decisions, Mastrogiovanni emphasized, should ideally be made long before someone actually retires. Advisors should discuss these choices with their clients as early and often as possible. In a system as complicated as Medicare, no one is likely to find a perfect path through the maze. But with an advisor’s help, they can at least see where they’re going.

“One of the things that the advisor can do is show the client, ‘Here are your options,'” Mastrogiovanni said. “Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to sit with an expert to help you and your spouse choose the best type of coverage?”

[ad_2]

Source link